The liver is the largest internal organ of the body that weighs 1-1.5kg which represents 1.5-2.5% of the lean body mass [1]. It serves as a chemical factory, excretory system, exocrine and endocrine gland [2]. One of the major functions is its capacity to metabolize, detoxify and inactivate endo- and exogenous compounds. Its strategic localization is therefore ideal to perform its functions since the majority of the blood supply is via the vena portae which drains blood from the gastrointestinal tract, gall bladder, pancreas and the spleen. The liver is therefore known to be “the gatekeeper” that determines whether certain absorbed particles will enter the body or not and thus operates as a filter. It is not surprising that the liver contains 14-20x106 specialized macrophages per gram rat liver [3], called Kupffer cells (KC), which remove foreign particles including bacteria, endotoxin, parasites and aging red blood cells [2].

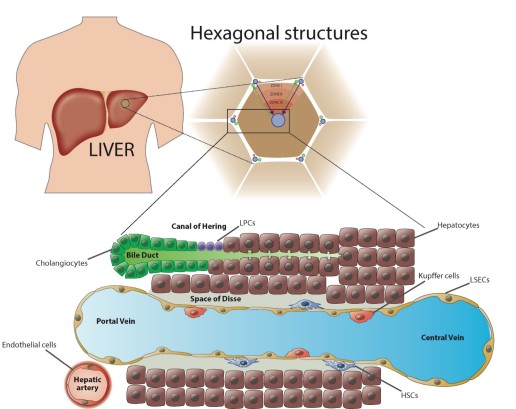

Another way of looking at the organization of the liver is by visualising the liver as numerous hexagonal structures or lobules which are framed by six portal triads (Figure 1). These triads exist of one vena portae, a hepatic artery (delivering oxygen rich blood) and a bile duct that drains bile from the canaliculi. A branch of the central vein is located in the centre of one hexagonal lobule, collecting blood coming from the vena portae and the hepatic artery. Importantly, bile flows the opposite way compared to the blood flow, creating specific zonations within each lobule (Figure 1). These zonations are created by the differences in blood content. Blood entering the lobule via arteria hepatica contains high concentration of oxygen and nutrients which reduces downstream. Periportal (around the portal triad) hepatocytes are therefore more specialized in oxidative metabolism whereas pericentral (centre of the lobule) hepatocytes detoxify drugs [2].

Bile is predominantly produced by periportal hepatocytes and contains, among other things, bile salts, bilirubin, drugs and toxins. All these compounds end up in the bile ducts and eventually exit the liver via the common hepatic duct. The epithelial cells of bile ducts are called cholangiocytes. These cuboidal cells contribute to bile secretion via the release of bicarbonate and water. The functions of bile are mainly excretion of drugs and toxic compounds into the duodenum and promoting the absorption of dietary lipids in the intestines. Bile acids are mainly reabsorbed by the gastrointestinal tract and returned via blood into the vena portae (= enterohepatic cycle) [1, 2].

Figure 1: Structure of the liver, zonations and the localization of the Canal of Hering.

The liver is situated in the upper-right portion of the abdominal cavity. It is organized in hexagonal structures defined by the portal triades with in the centre a hepatic vein. Blood flows from the portal vein and hepatic artery to the central vein and thereby forms different zonations (zone I, II and III). The blood flow is surrounded by liver endothelial cells (LSECs) and contains macrophages, called Kupffer Cells. The space between the LSECs and hepatocytes is called the “Space of Disse”, the niche of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs). The bile duct is situated next to the blood flow and bile is produced by hepatocytes which flows the opposite direction. The end of the bile duct is called the Canal of Hering, the niche of liver progenitor cells.

The liver is an adaptive and regenerative organ that is capable to restore its normal function in response to injury. However, this mechanism is interrupted during severe acute or prolonged injury leading to a loss of liver functions. Approximately 29 million people in the European Union suffer from a chronic liver condition. Liver diseases associated with mortality are at least as worrying as other diseases that are of major public health concern [4]. Liver cirrhosis, one of the most advantage liver diseases, is responsible for the death of 170.000 people each year in Europe [5].

Liver diseases can be distinguished into hepatocellular, cholestatic or mixed diseases. Hepatocellular diseases feature liver injury, inflammation and hepatocellular death while cholestatic diseases are caused by the inhibition of bile flow. Mixed models show both hepatocellular and cholestatic injury. Most presenting symptoms of liver diseases are jaundice, fatigue, itching, pain in the right upper quadrant, abdominal distention and intestinal bleeding. To diagnose patients with liver disease, a wide range of liver tests are available that makes it easy to rule out patients suspected of liver disease. Most commonly used biomarkers for the detection of liver injury are ALT and AST (alanine and aspartate aminotransferase), alkaline phosphatase, albumin and bilirubin. These different biomarkers can tell us whether the injury occurs hepatocellular or cholestatic, acute or chronic and whether cirrhosis or hepatic failure are present [1].

Because of the great regenerative capacity of the liver, extensive damage can remain asymptomatic. In response to liver damage, a normal liver response is performed by a controlled wound healing mechanism. During this process, a specialised cell type called a Hepatic Stellate Cell (HSC) transforms into an activated phenotype with the synthesis and remodelling of extracellular matrix (ECM). This process is called fibrosis or scarring of the liver which is characterized by an accumulation of ECM and the production of mediators to encapsulate the injury. Cirrhosis is the most advanced stage of fibrosis whereby this status of the liver is in most cases irreversible in contrast to fibrosis [6].

Strikingly, over 80% of patients suffering from cirrhosis develop hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) whereas the remainder continues with moderate to advanced fibrosis which still makes them susceptible to HCC [7]. Liver cancer accounts for 47.000 deaths per year in Europe and half a million is diagnosed each year worldwide [8, 9].

Most treatments for liver diseases are based on removing the ethiology, such as antiviral medication for hepatitis or change in life style for NASH. Liver transplantation is to date the last effective therapy for chronic liver disease.

Unfortunately, lack of liver donors, lifelong treatment with immunosuppressive agents and the high-risk transplantation limits the availability of liver transplantation as a treatment. Obviously, chronic liver diseases do not develop spontaneously. Leading causes of liver diseases are alcohol abuse, viral hepatitis B/C and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) [1]. Treating patients for hepatitis B/C, NASH or tackle abuse alcohol consumption is therefore essential to avoid further development of the disease.

References

1. Longo, D., L. and A. Fauci, S., Harrison's Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 17th ed. 2010, United States: The McGraw-Hill Companies. 738.

2. Boron, W. and B. EL, Medical Physiology, ed. E. Science. 2005.

3. Bouwens, L., M. Baekeland, R. De Zanger, and E. Wisse, Quantitation, tissue distribution and proliferation kinetics of Kupffer cells in normal rat liver. Hepatology, 1986

4. Blachier, M., H. Leleu, M. Peck-Radosavljevic, D.C. Valla, and F. Roudot-Thoraval, The burden of liver disease in Europe: a review of available epidemiological data. J Hepatol, 2013. 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.12.005.

5. Zatonski, W.A., U. Sulkowska, M. Manczuk, J. Rehm, P. Boffetta, A.B. Lowenfels, and C. La Vecchia, Liver cirrhosis mortality in Europe, with special attention toCentral and Eastern Europe. Eur Addict Res, 2010. 10.1159/000317248.

6. Friedman, S.L., Mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. Gastroenterology, 2008

7. Davis, G.L., J. Dempster, J.D. Meler, D.W. Orr, M.W. Walberg, B. Brown, B.D. Berger, J.K. O'Connor, and R.M. Goldstein, Hepatocellular carcinoma: management of an increasingly common problem. Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center), 2008

8. Parkin, D.M., F. Bray, J. Ferlay, and P. Pisani, Estimating the world cancer burden: Globocan 2000. Int J Cancer, 2001. 10.1002/ijc.1440.

9. Bosch, F.X., J. Ribes, M. Diaz, and R. Cleries, Primary liver cancer: worldwide incidence and trends. Gastroenterology, 2004. 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.011.